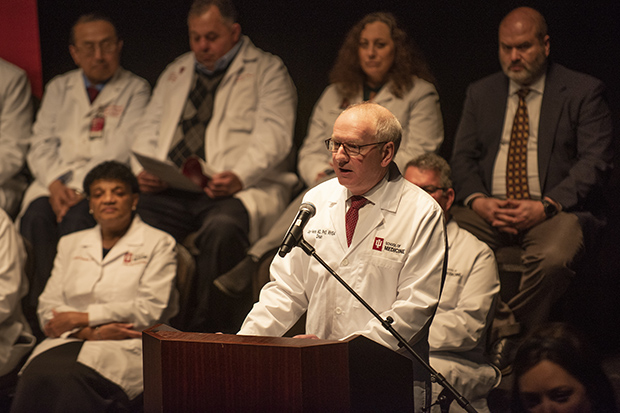

As daunting as that may have seemed, Jay Hess, MD, PhD, MHSA, arrived with an impressive list of credentials. He was a skilled pathologist with expertise as a teacher and researcher. His resumé included stints at some of the nation’s top medical schools—Johns Hopkins, Michigan, Penn, Washington University and one of the premier teaching hospitals at Harvard. And he came equipped with a set of priorities—outlined over three single-spaced pages—that may sound familiar to anyone who’s been paying attention over the last decade. It spoke about boosting the School of Medicine’s research funding to speed discovery and benefit patients, greater diversity, and building on strengths in neurosciences, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases with targeted investments in those priority areas.

In September, Hess will mark his 10th anniversary as dean, and it’s clear that IU School of Medicine is still following the course he outlined back in 2013.

During that span, the school’s annual awards for research funding from the National Institutes of Health more than doubled to nearly $215 million from $97 million. Much of the growth came in areas that are the school’s strengths, particularly neuroscience and cancer. But the research expansion is evident in every corner of the school—from obstetrics to otolaryngology and from pediatrics to surgery.

Despite being relatively new to fundraising, Hess took the case for the School of Medicine to donors around Indiana, to Florida, Arizona, and elsewhere. The fundraising campaign raised more than $1.7 billion, far surpassing the original goal. And the school’s endowment—vital for recruiting faculty, funding research, supporting scholarships and faculty chairs—has doubled to $1.17 billion from $579 million.

Academically, the school responded to the national doctor shortage by growing its enrollment 30 percent, mostly at regional campuses, firmly establishing itself as the nation’s largest medical school. To respond to accreditation concerns about a lack of consistency at those campuses, the school adopted a common curriculum, and ensured that students learn from its best teachers, no matter which campus is their home.

Hess still carves out time to first-year medical students in a course on fundamentals of health and disease.

HESS NOT ONLY found his way to those regional campuses but saw major facility upgrades with new buildings in West Lafayette, Evansville, and Bloomington.

In Indianapolis, he’s laid the groundwork for a new medical education and research building that will be the largest construction project in school history.

As it expanded, the student body has grown more diverse while its performance has improved. When Hess arrived, the share of students from populations underrepresented in medicine was 13 percent. In his tenure, that share rose higher than 20 percent, before slipping slightly. While some key administrative posts now have more women and people of color and the school has inched above the national average for faculty diversity, Hess acknowledges that more progress is needed in diversifying the faculty and that continues to be a priority.

Beyond numbers, the school has progressed in other ways. Researchers developed a new FDA-approved treatment for a debilitating bone disease called XLH, which affects children. The school became home to one of two NIH-funded centers pegged to discover treatments for Alzheimer’s. The IU Melvin and Bren Simon Cancer Center joined the nation’s elite cancer centers by earning the National Cancer Institute’s designation for being “Comprehensive,” an honor that made it into the center’s name.

The school’s reinvigorated cardiovascular research program may revolutionize the way we treat the aftermath of heart attacks. The school has become a powerhouse in biostatistics and data science, established a new center to tackle psychiatric disorders of children, and planted a flag in the rapidly evolving field of regenerative medicine.

“The data speak for themselves,” said IU School of Medicine Dean Emeritus D. Craig Brater, MD, Hess’s immediate predecessor. “If you look at the classic three disciplines in academics—teaching, research, and patient care—it seems that over the last 10 years, all of those are hitting on all cylinders. And Jay gets the credit for that.”

Steve Becker, MD, who leads the Evansville campus, said Hess quickly appreciated the need to expand residency slots in Indiana. And his emphasis on expanding funding for research has been “mission critical.” “He will be viewed among our most consequential deans,” Becker said, “the sort that launched the school into the 21st century.”

Discussing his decade at IU School of Medicine, Hess gives a nod of thanks to Brater and his other predecessors as dean. He credits the talent and dedication of researchers, teachers, and staff. He appreciates the key role of philanthropy in major breakthroughs. And, given the enormity of the school and its many functions, he’s learned a key lesson: “There is almost nothing you’re going to get done without a lot of other people working alongside you.”

Hess meets with Jodi Skiles, MD, and Sherif Farag, MD, PhD, who rolled out an immunotherapy program for pediatric patients.

CHOSEN FROM A field of more than 50 candidates, Hess became just the second IU School of Medicine dean (with Charles Emerson, MD, in 1911) who didn’t emerge from within the school’s own ranks. While some saw an outsider, others saw someone with a fresh perspective.

“Jay was at places we had always said were the kinds of places to which we want to aspire—the University of Michigan and (Johns) Hopkins and those places,” Brater said. “By living in those environments, he knew what it meant and what it took to get there. I think it’s very healthy.”

Tatiana Foroud, PhD, now the school’s executive associate dean for research affairs, was a member of the search committee in 2013. She said there’s value in “having seat time” at a place and the ability to understand its rhythms, quirks, and key players. “But it’s also really valuable to bring in people from the outside,” Foroud said. “You also need a totally new way to look at things.”

While his predecessors had worked to grow research funding with some success, Hess found that growth had plateaued—and the school ranked 41st nationally in NIH funding. From early on, he made it a priority to grow those totals to ensure IU’s place in the nation’s research story, and to help patients. He supported investments in core research facilities. He invested in current faculty and in recruiting people with curiosity and a drive to work hard. And he promoted mentoring for early-career researchers just getting established. “At a high level, medical schools are largely judged by their NIH funding. It is a proxy for excellence,” he said. “The better your reputation, the more people want to come and work at your school. That floats a lot of boats.”

Hess has worked to better align the School of Medicine with IU Health during his tenure. Today, the school is folded into the provider’s master plan and received a long-term lease for property where it is constructing a new medical education building and research tower.

ONE AREA WHERE his outsider’s viewpoint may have helped was in the school’s relationship with Indiana University Health.

When he arrived, it wasn’t clear to Hess where IU Health was headed or the enormous effort it would take to bring their visions into line. Soon, he learned IU Health had plans to close University Hospital and move its functions to a new hospital near IU Methodist. This, Hess said, was an “inflection point.”

“They were essentially moving away from the university’s center of gravity,” he said. “I thought it was important that the School of Medicine be front and center there. We’re an academic health system. The School of Medicine is an integral part of that.”

Hess advocated for the school’s inclusion in IU Health’s master plan, and, in the end, the school was given a long-term lease for property where the new medical education and research building is being constructed. IU Health is contributing substantially to its construction.

The closer ties were also evident at the end of 2021, when IU Health made a $400 million gift to the school, money that will be aimed at building diversity, recruiting faculty, and investing in research. These are indicators, he said, of how the relationship has improved. “We are interdependent. Our success is their success, and vice versa. Ultimately, everything we do is about improving health in the state,” Hess said.

Hess credits much of the progress to IU Health President and CEO Dennis Murphy. “We couldn’t have accomplished what we have without Dennis’ leadership and support. I don’t think you’ll find a medical school dean and hospital CEO who work better together than we do.”

Murphy came to the health system in 2013 and assumed leadership in 2015. He describes Hess as a “collaborative and compelling leader” who has taken the school to new heights in ranking and reputation.

He said he and Hess have developed a common vision and goals aimed at creating a tighter alignment between the two and improving the state’s health. “From the start, Jay and I shared a belief that by working together, we could make (the school) and IU Health a national leader in academic medicine,” Murphy said.

Distinguished professor and former cancer center director Pat Loehrer, MD, said Hess came at a time when the school-health system partnership was at a difficult stage. “I think he’s done an excellent job of navigating that,” Loehrer said. “I think the school is very well placed.”

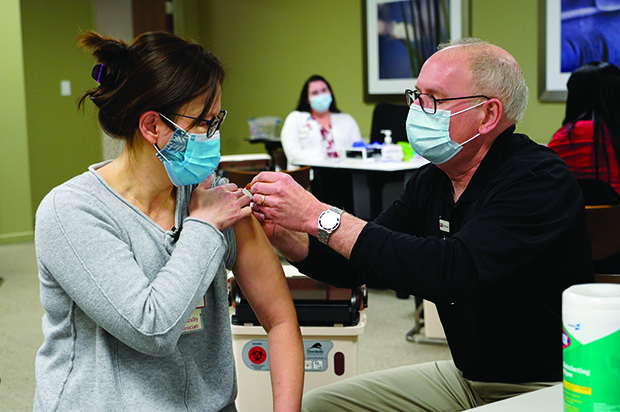

Hess led Indiana University’s response to the pandemic. This role included taking time to join medical students in administering early doses of COVID-19 vaccines.

The partnership still faces a steep climb when it comes to improving Indiana’s health. The state ranks 35th in overall health, according to America’s Health Rankings 2022 report. While Hess points to some improvement in infant mortality numbers, he recognizes that Indiana faces many health challenges.

Indiana has the fifth highest smoking rate and 12th highest rate of obesity. But there are policy challenges, too. Hess said the state’s investment in public health is low compared to the rest of the country and Indiana has been reluctant to make evidence-based changes, such as increasing the cigarette tax. And he’s concerned about the doctor-patient relationship. “I think the patient and the physician are the best informed to make decisions that impact the patient’s life,” he said. Moving forward, the school and its faculty need to be engaged in the public discussion, he said.

“It’s very difficult to improve the health of this country without getting involved in legislation and policy,” he said. “Our whole reason for being is to improve the health of people. If we have evidence to say, ‘If you do this, our people will be healthier,’ I think we have a responsibility to at least make people aware of that and advocate for our patients, being careful to stick to the data and the science.”

Hess has been an advocate in his own way. He’s marched in Indy Pride parades in support of the LGBTQ+ community. In the aftermath of the 2020 murder of George Floyd and the national reckoning on race that it prompted, he appointed professor emeritus Pat Treadwell, MD, as a special advisor and the school’s chief diversity officer. The move, she said, was no window dressing. The school created a task force on diversity and began holding town halls, revised its honor code to oppose racism, and raised the profile of inclusivity and respect.

“I’ve been here for five deans, and he has had the strongest commitment to diversity of all the deans that I’ve worked with,” Treadwell said. “My appointment was evidence of that.”

As Treadwell stepped aside and toward retirement, Hess in January appointed Chemen Neal, MD, to be the school’s first executive associate dean for diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice, as well as chief diversity officer.

Of course, 2020 also brought the arrival of the first documented cases of COVID-19 in the United States. At the outset, Hess saw the gravity of an airborne virus that could spread before a patient shows symptoms. Soon, IU President Michael McRobbie appointed him to lead the committee guiding IU’s response to COVID. When vaccines arrived, he joined a small army of students who were administering them around the state. For Treadwell, it was an example of a leader willing to gain perspective on the big picture by viewing them from the ground level. She added, “I think it is because of his sincerity, his genuineness, and integrity.”

After 10 years on the job, Hess remains excited about the next steps in IU’s evolution: opening a new medical education building, pushing into the top 20 for NIH funding, and finding ways to improve social determinants of health.

HESS IS IU School of Medicine’s 10th dean.

The length of his tenure falls just in the middle of the pack of previous deans, which skewed longer before the 1950s. Yet his 10 years is far above the national average for medical school deans around the country today, where the norm is closer to 4½ years. Some people, he said, aren’t a good fit for a job which can be demanding, complicated, and time-consuming, others get “crosswise” with stakeholders, suffer burnout, or move to more attractive jobs. “I think the ones who stay,” he said, “stay because they are getting things done. That’s a big part of what keeps me here.”

Looking ahead, Hess sees more work to do. The new medical education and research building is due to open in 2024, there’s a re-accreditation visit in 2025, and the new IU Health hospital is due to open in 2027. He wants to see all that to fruition. He also has loftier goals—to see the school reach the top 10 in NIH grant funding for public medical schools and top 20 of all medical schools, public or private. And he is hopeful the school will make truly historic new discoveries, in areas like Alzheimer’s disease and others.

As to what he’s learned on the job, there are a few things. From students, staff, faculty, alumni, donors, and corporate and political leaders, he found that there are plenty of stakeholders, whose interests are sometimes not aligned.

“You’re going to get buffeted every day by a lot of things, but, ultimately, you have to remember what the results are that you’re looking for,” he said. “You’ve got to be able to sleep at night—being fair with people, being equitable, feeling that you did your best. And wherever possible, try to get along.”